NASA readies to deflect asteroid in key test of planetary defense

A small point of light that starts to fill out the screen, revealing a never-before-seen asteroid, before the images abruptly stop as the spacecraft is lost.

That's what NASA is hoping to see Monday as it takes aim at a space rock to slightly deflect its orbit -- a historic test of humanity's ability to stop a cosmic object from devastating life on Earth.

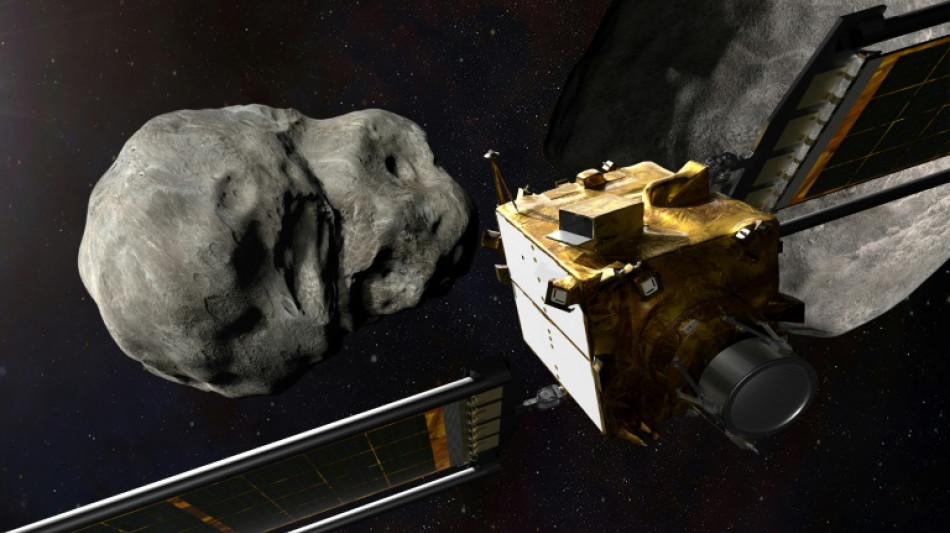

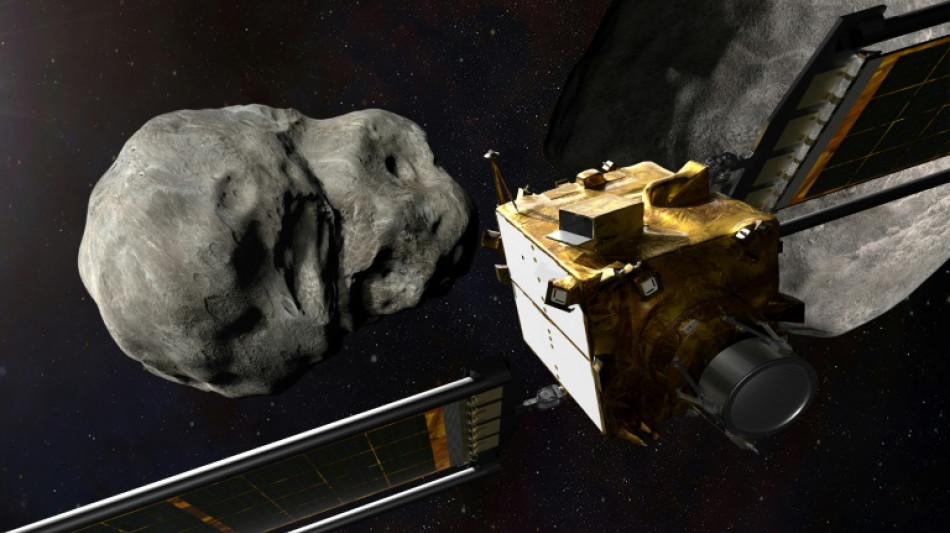

The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spaceship launched from California last November and is fast approaching its target at roughly 14,500 miles (23,500 kilometers) per hour.

"Today we're taking a giant step in planetary defense," said NASA chief Bill Nelson in a video statement ahead of projected impact.

To be sure, neither the asteroid moonlet Dimorphos, nor the big brother it orbits, called Didymos, pose any threat as the pair loop the Sun, passing about seven million miles from Earth at their current "minimized" position.

But NASA has deemed the experiment important to carry out before an actual need is discovered.

If all goes to plan, impact between the vending-machine sized spacecraft and the 530-foot (160 meters) asteroid -- roughly comparable to an Egyptian pyramid -- should take place at 7:14 pm Eastern Time (2314 GMT), viewable on a NASA livestream.

By striking Dimorphos head on, NASA hopes to push it into a smaller orbit, shaving 10 minutes off the time it takes to encircle Didymos, which is currently 11 hours and 55 minutes -- a change that will be detected by ground telescopes in the days or weeks to come.

The proof-of-concept experiment will make a reality of what has before only been attempted in science fiction -- notably in films such as "Armageddon" and "Don't Look Up."

- Technically challenging -

As the craft propels itself autonomously for the mission's final four hours like a self-guided missile, its imager will start to beam down the very first pictures of Dimorphos, before slamming into its surface.

"What we're looking for is loss of signal. And what we're cheering for is a loss of the spacecraft," said Bobby Braun of Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory.

Minutes later, a toaster-sized satellite called LICIACube, which already separated from DART a few weeks ago, will make a close pass of the site to capture images of the collision and the ejecta -- the pulverized rock thrown off by impact.

LICIACube's pictures will be sent back in the next weeks and months.

Also watching the event: an array of telescopes, both on Earth and in space -- including the recently operational James Webb -- which might be able to see a brightening cloud of dust.

The mission has set the global astronomy community abuzz, with more than three dozen ground telescopes participating, including optical, radio and radar.

"There's a lot of them, and it's incredibly exciting to have lost count," said DART mission planetary astronomer Christina Thomas.

Finally, a full picture of what the system looks like will be revealed when a European Space Agency mission four years down the line called Hera arrives to survey Dimorphos' surface and measure its mass, which scientists can currently only guess at.

- Being prepared -

Very few of the billions of asteroids and comets in our solar system are considered potentially hazardous to our planet, and none are expected in the next hundred years or so.

But wait long enough, and it will happen.

We know that from the geological record -- for example, the six-mile wide Chicxulub asteroid struck Earth 66 million years ago, plunging the world into a long winter that led to the mass extinction of the dinosaurs along with 75 percent of all species.

An asteroid the size of Dimorphos, by contrast, would only cause a regional impact, such as devastating a city, albeit with greater force than any nuclear bomb in history.

How much momentum DART imparts on Dimorphos will depend on whether the asteroid is solid rock, or more like a "rubbish pile" of boulders bound by mutual gravity -- a property that's not yet known.

The shape of the asteroid is also not known -- whether, for example, it's more like a dog bone or a diamond -- but NASA engineers are confident DART's SmartNav guidance system will hit its target.

If it misses, NASA will have another shot in two years' time, with the spaceship containing just enough fuel for another pass.

But if it succeeds, the mission will mark the first step towards a world capable of defending itself from a future existential threat.

P.Claes--JdB